Interview - Vicki Fishlock, ATE

In honour of World Elephant Day, I have a very special interview with an elephant expert, enjoy! :)

A key component of wildlife photography is to know you subject (KYS). Knowing more about your subject will allow you to preempt situations and shots rather than reactively taking them. It will allow you to give more meaning to you images as you understand the significance of a situation better and will help you produce more individual images.

It is also vital for the safety and well being of the subject and your self. So, who better to ask about a subject than the experts! I hounded Vicki to give me this interview and she kindly agreed, along with a KYS profile on elephants I will be posting soon (stay tuned).

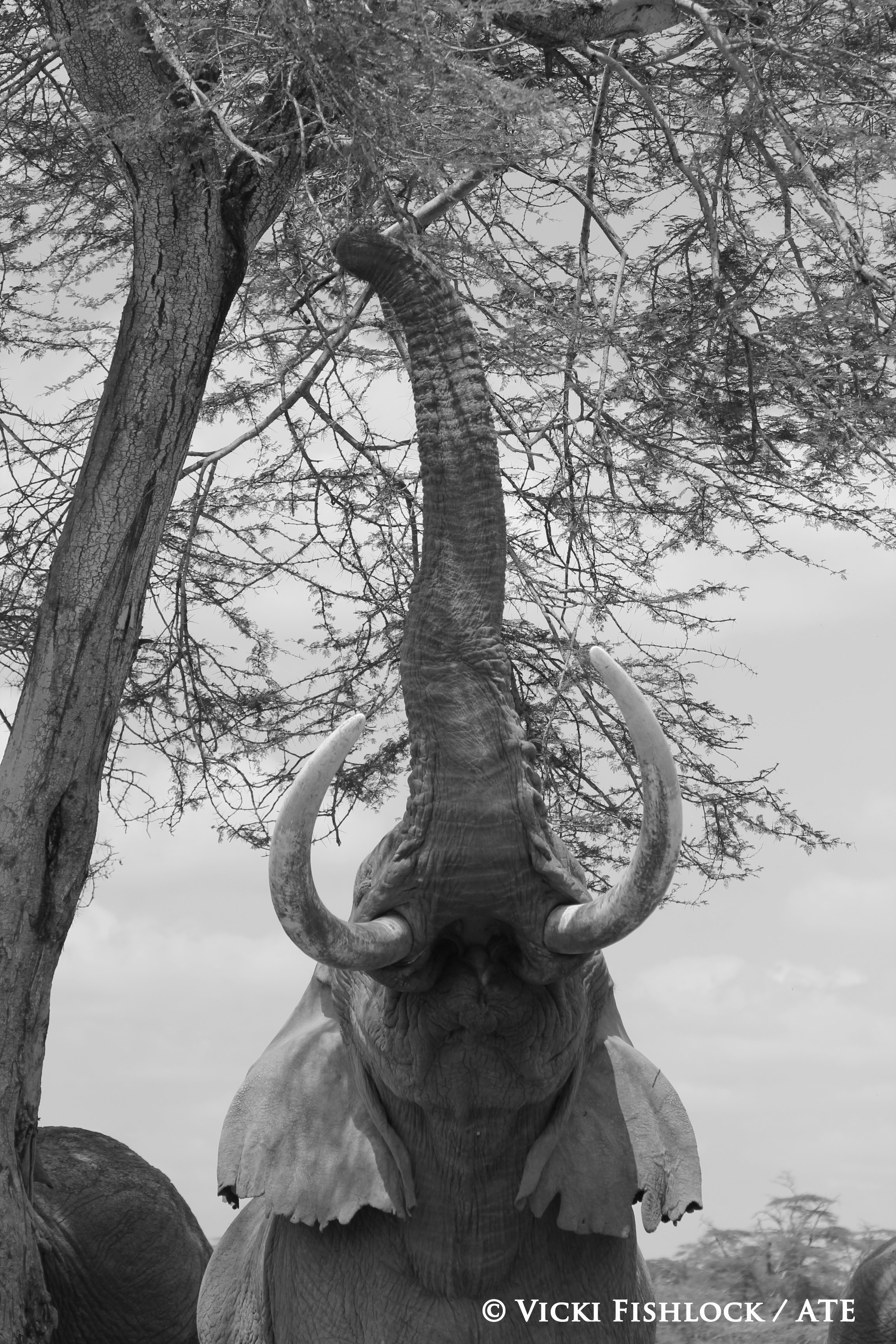

Moreover, despite Vicki's fervent claims that "I am not a photographer", she has amassed a stunning set of images during her research. She kindly agreed to share a few with us in a gallery at the end of the interview.

BONUS VIDEO: You can check out Vicki the heroine in the video below when she and the ATE team rescue a trapped calf! This video featured on the BBC website and has had ~5.5 million views! You're a star Vicki... :)

We rescued this young eight months old calf early this week. Luckily the report came in early in the morning and we were able to get there quick before the mother was forced to leave by herders arriving to water their cattle.

Anyway, without further ado, lets hear from Vicki herself!

Researchers name: Vicki Fishlock

Affiliation: Amboseli Trust for Elephants (ATE)

Funding: International Fund for Animal Welfare

Research location: Amboseli, Southern Kenya

Research Subject: African Bush Elephant (Loxodonta africana). [It must be noted she is also an expert in African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) too!]

Research aim: Patterns of reproductive and social recovery after matriarch (leadership) loss

Vicki, why are you interested in Elephants? What is it about them that make you get up in the morning to study them?

Elephants got me interested because they have such complex social lives, and I was interested in the costs and benefits of living in such an intricate world. But what really made me fall for them is how individual they are: I’m totally hooked now because everything depends on who – it’s a soap opera, and I never tire of finding out what happens next to whom. Elephants have individual characters and personality; they really are “who” not “what” animals. Much of their behaviour is focused on identifying themselves as individuals, and reaffirming their relationships with one another. Like humans, their lives unfold over very long periods, and they maintain relationships for lifetimes. They’re impressive, charismatic and delightfully fun animals to spend time with. I have taken a lot of people out to introduce them to elephants, and every single one of them has been profoundly affected by their connection to the elephants – in many cases that connection came as a complete surprise. They are very special.

Can you expand on the aim of your project? What is it you are trying to find out, and why is this important?

Amboseli is probably the closest thing we have left to an undisturbed elephant population. Although the elephants increasingly share space with humans, they are well-protected and their behaviour hasn’t been drastically modified. In 2009, a terrible drought killed most of the animals in Amboseli; thousands of cattle, wildebeest, zebras and other species died. The elephants lost hundreds of members of the population, especially old females, some of whom had led their families for more than three decades. Understanding how elephant families recover from the loss of experienced leaders, who are important repositories of social and ecological knowledge, is important for understanding how elephant populations can cope with the loss of these leaders, because poachers are leaving elephant families decimated across Africa. We have already seen that this can have downstream effects for survivors that last for decades, but we haven’t seen how elephants recover from those losses. Understanding recovery is going to be critical for predicting where elephants will be able to recover and thrive once more, given our limited resources for conservation, and increasing human populations.

How do you answer this question? What data is it you are collecting and how do you collect it?

Apart from continuing our long-term monitoring – who is where, with whom, and when do females give birth – I am becoming increasingly interested in elephant leadership and negotiation. Elephants have a fission-fusion society, so family members and friends don’t spend all their time together. It means they can balance the benefits of valuable long-term relationships against the costs of living in a group where there might be competition, or conflicts of interest about where and when to access resources. I’m really becoming fascinated by the ways elephants reach consensus (or not) about where and when to travel. I spend a lot of time waiting for families to make movements – even on a small scale – recording which individuals initiate the movement, who they elicit responses from, how often they succeed in getting the family to move with them, how often they go off on their own if they can’t get support. It’s a lot of sitting with the elephants, and driving with them. I have twelve study families I’ve been working with closely over the past five years, but now I’m drawing to the end of the grant, I spend more time on the computer than with them.

What does ‘an average’ day entail?

If I’m heading to the field, I’ll get up around 0630, have some tea and figure out which families I want to work with that day. Based on when I or my colleagues last saw them, I will head to a likely area, hopefully before they decide which area they want to use for the day. Luckily elephants are active through the night, and then often have a little nap in the first part of the day, so I can catch up with them then. We don’t have permission to be out working at night, and it would severely limit the data I could capture anyway.

What, if you can share, have you found out?

Elephants don’t fit in boxes!!! Analysing these kinds of data is incredibly tricky because there’s a lot of individual variability, and you never get truly independent data points because elephants have these long-standing relationships that affect their responses. Even our reproductive statistics are affected by left- and right-censored data issues, and incomplete individual trajectories. I’ve done some network analyses that lets me examine how the loss of matriarchs affect relationships between families; there are clear effects of losing key individuals, which causes bonds between families to weaken during a recovery period.

Why should other people be excited by your work and what is the impact to the general public?

I think learning about social complexity in other species teaches us a lot about ourselves. Elephants are critical because they are ecosystem engineers, and vital components of their habitats; if elephants are removed from an area, plant and animal communities change. They have correspondingly huge effects on their areas, and on the people that share space with them. They are also long-lived, so their lives unfold on a similar timeframe to humans. I think understanding how individual variability builds into the population level processes that shape ecosystems is a really important question for understanding how ecosystems can buffer the effects humans have on them. Understanding elephants also helps us promote coexistence between elephants and people.

What is your most memorable time had with the Ele's?

Elephants often make me laugh, but they move me to tears as well. I started talking to the elephants as I approached them because my car was staying around so long, after a while they started to pay attention to me and wonder what I was still doing there. Most of the time they ignore me completely when I talk to them, but it gives them a verbal cue about how the car is going to behave, so I’ve been doing it for years. But when I saw the EB family after they had been travelling and out of the Park for several months, my greeting had a massive effect; Enid raised her head and rumbled a greeting at me and then all the family walked past the car, so close I could have touched them. I felt so special in that moment, to be known and recognised by a wild elephant family, but later I decided she could have been communicating with someone else (elephants use infrasound, so there’s always a lot going on that we can’t hear). A few days later I went to use the camp shower and there were elephants close by. We don’t have a fence, so the animals can come into camp but they usually avoid it during the day when people are active. It was getting dark and cold so I slipped in and started the water running, thinking that would get them to move away. Enid backed out of the bushes and when I saw her I said hello; she rumbled a greeting at me and stood feeding 5m away while I washed my hair and chatted to her. Now I know that when she says “hello”, she really is talking to me.

Where can we find out more information or follow your research?

You can find out more by visiting our Facebook page, website or on my blog for IFAW

How can we help?

The long-term monitoring of the Amboseli Elephants is entirely reliant on donations. By visiting our website, you can find out more about ways you can support our work. Spreading awareness about why elephants are special and threatened is easy – sign petitions against ivory, share stories on social media about why they are remarkable. Better yet, come and visit them in their natural habitats, and support responsible tourism.

I am sure you will all agree that these are fantastic images indeed...

Many thanks to Vicki, and we wish you and your big-eared friends the best of luck! :)